Understanding the Electrical Conductivity of Aluminum

Aluminum is everywhere, but have you ever wondered how well it conducts electricity and why engineers choose it over copper?

Aluminum has excellent electrical conductivity, making it a popular alternative to copper in many industrial applications where weight and cost matter.

While copper remains king for many electrical tasks, aluminum offers serious advantages. This post explores aluminum’s conductivity, compares it with other materials, and explains key values like the k value and electrical grade.

What is the electrical conductivity of aluminum?

Aluminum is widely used, but its conductivity often surprises people who assume copper is always better.

The electrical conductivity of aluminum is about 3.5 × 10⁷ S/m1 (siemens per meter), which is around 61% that of copper.

The conductivity value of 3.5 × 10⁷ S/m reflects pure aluminum at room temperature. This level of conductivity is sufficient for many industrial uses, including power transmission lines, where aluminum’s lower density and cost provide clear benefits.

What factors affect aluminum’s conductivity?

- Purity: High-purity aluminum has better conductivity. Alloys tend to reduce conductivity due to additional elements.

- Temperature: Like most metals, aluminum’s conductivity decreases as temperature increases.

- Oxidation: Aluminum naturally forms an oxide layer, which is non-conductive. While this layer is thin, it can affect surface-level electrical contact.

Here’s a simple comparison table:

| Material | Conductivity (S/m) | Relative to Copper |

|---|---|---|

| Copper (pure) | 5.96 × 10⁷ | 100% |

| Aluminum (pure) | 3.5 × 10⁷ | 61% |

| Iron | 1.0 × 10⁷ | 17% |

Despite being less conductive than copper, aluminum is much lighter. This makes it a good fit in applications like long-distance power lines, aircraft, and high-volume machinery housings where weight matters.

Is aluminum a good conductor of electricity?

Some buyers hesitate about aluminum because they’ve heard it’s "worse than copper." But is that the whole picture?

Yes, aluminum is a good conductor of electricity2 and is widely used in electrical applications like power cables and busbars.

The perception that aluminum is a “poor” conductor is mostly due to its comparison with copper. But in practice, aluminum is good enough for most uses. For instance, in overhead power lines2, aluminum is often the first choice. Why? Because it weighs about one-third as much as copper and is significantly cheaper.

Where does aluminum outperform copper?

- Cost: Aluminum is about 60% cheaper than copper.

- Weight: Copper is 3.3 times heavier than aluminum.

- Corrosion Resistance: Aluminum naturally resists corrosion due to its oxide layer.

Of course, there are challenges too. Aluminum connections can loosen over time due to thermal expansion. That’s why proper fittings and installation practices are important.

In short, aluminum is not only a good conductor—it’s a strategic material choice in many sectors. Engineers often design with it specifically because of its combination of conductivity, weight, and cost.

What is the k value of aluminum?

You might hear engineers or datasheets talk about the "k value"—but what does that actually mean?

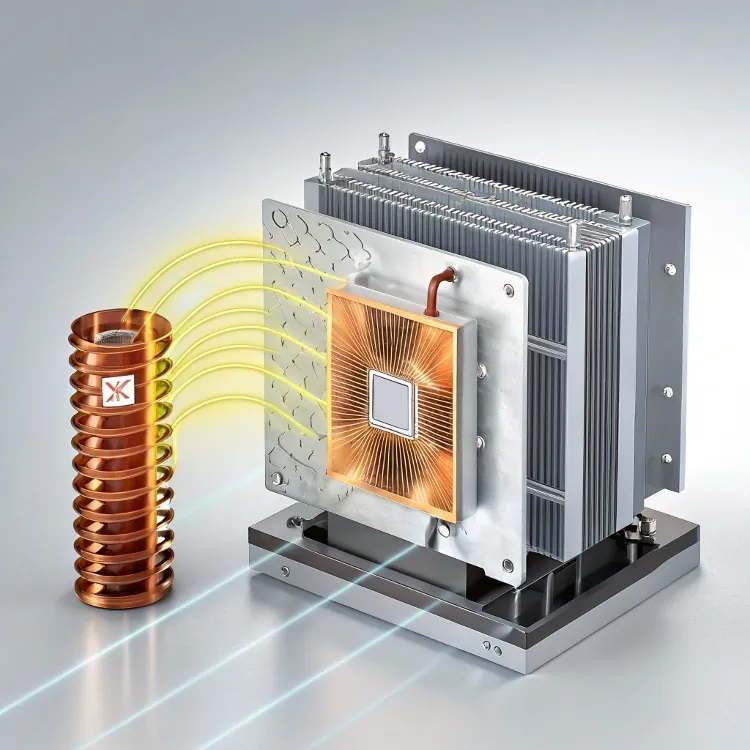

The k value of aluminum usually refers to its thermal conductivity, which is about 237 W/m·K, one of the highest among metals.

Although this article focuses on electrical conductivity, thermal conductivity3 often comes into the discussion because in metals, heat and electricity move through the same free electrons. Aluminum’s high k value4 means it not only carries current well but also dissipates heat quickly.

Why does thermal conductivity matter in electrical components?

- Heat dissipation: High-power components get hot. Aluminum helps cool them quickly.

- Thermal stability: Uniform heat spread reduces thermal stress.

- Design efficiency: With aluminum, manufacturers can reduce weight without sacrificing performance.

For example, aluminum is the go-to material for LED lighting heat sinks, power supplies, and inverter housings. When I work with clients building solar power systems or machinery, aluminum profiles often double as both structural and thermal elements—thanks to that high k value.

What is the electrical grade of aluminium?

You might see terms like "EC grade aluminum" or "electrical-grade alloy"—what do they really mean?

Electrical-grade aluminum is typically 1350 (also known as EC grade), which contains at least 99.5% aluminum and offers high electrical conductivity.

Aluminum grades for electrical purposes are specially selected to maximize conductivity while still being practical for manufacturing.

Common electrical grades:

| Grade | Purity (%) | Conductivity (% IACS) | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1350 (EC)5 | ≥ 99.5 | ~61% | Power cables, busbars |

| 6101 | Alloyed | ~57% | Structural + conductive use |

| 6061 | Alloyed | ~40% | Mechanically strong sections |

In my factory, when we receive requests for busbars or custom conductive profiles, we usually recommend 1350 or 6101, depending on whether mechanical strength or max conductivity is more important.

Also, many clients prefer to anodize or coat these profiles. We support multiple surface treatments while maintaining conductive performance through precise machining and design optimization.

Conclusion

Aluminum offers solid electrical performance, especially when you factor in weight, cost, and versatility. It’s more than just “good enough”—it’s often the smarter choice.

-

This specific conductivity value is essential for grasping aluminum’s performance in various applications. Check this link for a deeper explanation. ↩

-

Discover why aluminum is the material of choice for overhead power lines and its advantages over copper. ↩ ↩

-

Exploring thermal conductivity helps in understanding how materials like aluminum manage heat, essential for various applications. ↩

-

A high k value indicates superior thermal and electrical performance, vital for effective engineering solutions. ↩

-

Explore the significance of 1350 EC grade aluminum in electrical applications and its benefits for conductivity. ↩